Introduction

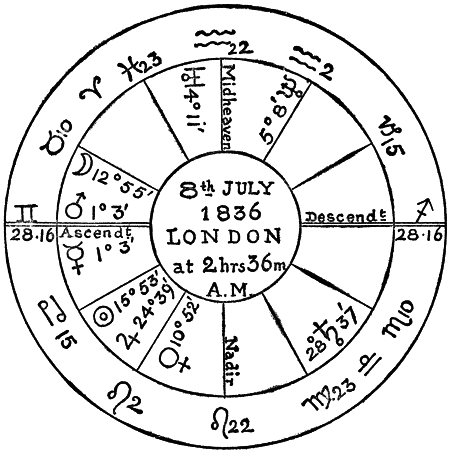

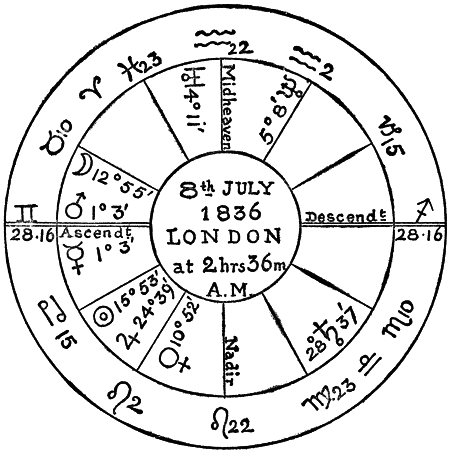

Currently, something of a divide exists in divination practices. On the one hand we have astrology. Consider this natal chart, for example (Sepharial). In the twelfth house, located on the left directly above the horizontal ascendant line, we find both the moon and Mars. The eleventh house just above it, though, is empty, as are three consecutive houses on the right. These kinds of arrangements are typical in natal charts, where some houses may have multiple planets while others have none.

On the other hand, with sortilege methods of divination, such as tarot, runes, and ogham, the typical techniques produce a different pattern. The layout has one or more positions, and one symbol is drawn for each. In a Celtic cross spread, for example, one symbol is drawn for each of the ten positions. The key difference is that each position always has exactly one symbol, unlike in astrology. Often this is fine for providing the answers we need.

Sometimes, however, we may want a more detailed picture. We may find ourselves in a situation where some aspects are influenced by many factors and others by few or none. One quick alternative that works with sortilege methods is to grab a handful of tokens instead of just one for each position. Again, sometimes that may be enough. Other times, though, we may want to use a more systematic approach, especially one that allows for empty positions.

The method introduced here can meet those needs. The basic method allows for positions to have zero, one, or multiple symbols. The variations discussed later allow the seer to further adjust the method to meet the needs of that particular divination. In honor of the city where I first used this method, I refer to it and its variants as the Lansing method.

What You Need

The Lansing method works with any set of divination symbols where you can tell reversed symbols from upright ones. One of the intermediate steps, which will be explained shortly, will rely on separating upright and reversed symbols. You do not have to read reversals in your final interpretation, though you certainly can if you want.

You will also need some way of randomizing the symbols, including their upright/reversed orientation. For symbols on pieces of wood or stone, a bag large enough to thoroughly mix them with a shake works. For symbols on cards, you will need to shuffle them carefully to ensure you randomize the orientations.

Lastly, you need to decide on a spread layout. This could be just a single position for a quick reading, a three position past/present/future layout, the 12 astrological houses, or whatever other spread makes sense for your purpose.

Basic Method

The basic process consists of two steps, which you will repeat for each position in your layout. The first step, the reduction step, will start with your full set of symbols and repeatedly eliminate any of them not needed for that position. The second step, the casting step, produces the final result.

To understand the reduction step, a useful analogy is sending out invitations to a party. Initially, everyone gets an invitation and is a potential guest. Some will decline the invitation immediately due to schedule conflicts or other reasons. Those folks are no longer potential guests. Based on those responses, other people may decline as well – if someone knows their spouse or best friend is not going, or if the person they rely on for a ride is not going, they are likely to decline the invitation too.

After each cycle of responses, as more people back out of the party, the guest list shrinks, until one of two things happens. It may be that eventually everyone declines the invitation; no one will be coming to that party. The party may be a failure in our analogy, but in divination this is not a problem. Just as many of us have empty houses in our natal charts, the more general case is no different – in the chart we are casting, there simply will not be anything happening in that particular position.

The other possibility is that after a cycle of responses, no one new has backed out of the party. This means we have a final list of guests, since no one left on the list had a reason to back out. All of the remaining symbols, then, will fill that position in our layout.

So, to bring our analogy back to divination, shake all of your symbols in your bag or shuffle all your cards together. Ask, “which symbols wish to remain in the casting for the first house?” or whatever appropriate description of that position fits your layout. Then empty out your bag or stop shuffling. At this point, just look at whether symbols are upright or reversed. For this purpose, we read upright as “yes” and keep those symbols; reversed symbols have responded “no” and get removed from this position. We repeat this process on an ever shrinking set of symbols until we reach one of the two endpoints: either all symbols get removed – meaning we move on and start fresh at the next position – or we get a set of symbols that are all upright. Either way, the reduction step ends for that position.

You only need the casting step if you actually read reversals in your divination. The reduction step used uprights and reversals as a simple yes/no system, but that does not mean you need to consider reversals in your final interpretation. If you intend to disregard reversals, you are done with this position – you know which symbols are there, so write them down and move on to the next position.

If you do read reversals, though, we need to do one last shake up of the bag. Otherwise, we could never end up with reversed symbols because of how the reduction step works. Put the remaining symbols in your bag, shake it up, say “I am now casting the reading for the first house” or similar words to that effect, and turn them out. The set of symbols remains the same, but this extra step has reintroduced the possibility of reversals in your reading.

Continue through each position, reducing (starting with the full set for each position) and – if needed – casting, until you complete your layout. Once you have filled each position, perhaps with blank spaces for some, you have completed the chart. It is then up to you to interpret the resulting symbols for each position.

Variations

Applying the basic method, a particular symbol in your divination set may appear in one position, multiple positions, or may not appear in your chart at all. For many purposes, this may serve our purposes fine. However, if you want something more akin to an astrological natal chart, the method can be adapted to achieve this.

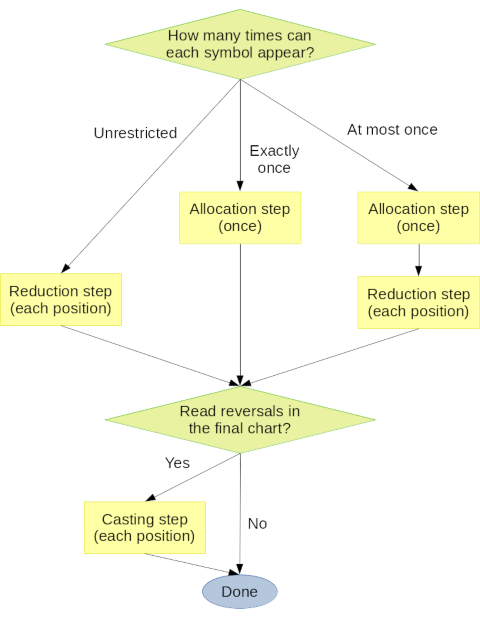

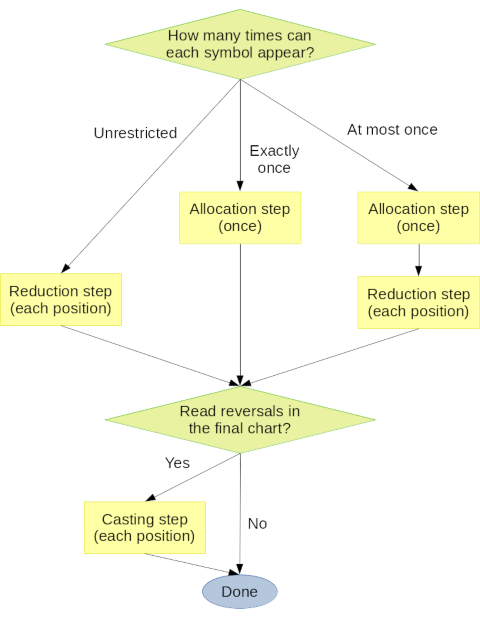

There are three outcomes we can accomplish easily. Using the basic process discussed earlier, each symbol is unrestricted in how many times it appears (perhaps nowhere, perhaps multiple places). Alternatively, we can restrict symbols to either appear exactly once or at most once in the chart, if those would suit the reading better. Either way, we accomplish this by adding one extra step before we start reducing: the allocation step. Unlike the reduction and casting steps, we only do the allocation step once for the entire layout, not position by position.

With the allocation step, we assign each symbol to exactly one position. The multi-sided dice used for role-playing games work well for this – a 12-sided die (“d12”) works perfectly for the 12 astrological houses, for example. If you do not have such dice, a phone or computer can also provide random numbers. Just roll the die for each symbol, and the result is the position it gets allocated to.

For the at most once variant, proceed with the reduction step as before, except starting with just the symbols allocated to each position instead of the entire set. For the exactly once variant, skip the reduction step. In any case, finish each position with the casting step if you want reversals in your layout.

As a visual summary, this flow chart shows the steps for each variant.

There is one minor consequence of this process that might be helpful to point out. Since the exactly once variant does not use the reduction step, you can apply it to systems that do not have an upright/reversed distinction. For example, astrological charts effectively use that variant, where the relative positions in the sky serve as the allocation step.

Example

I used the basic Lansing method to cast a chart for the success of this article. I read reversals, but all the ogham happened to come out upright anyway in this case. My layout was simple. The first position represents factors helping the success of this article in spreading knowledge of the technique. The second position represents factors hindering its success. The third is the hinge or the pivot – what factors will decide the balance between success or failure.

Helping factors: Ailm, Ur, Nion

Hindering factors: none

Deciding factors: Ailm, Uillean

Encouragingly, three factors are helping drive the success of this project. Ailm points to the big picture, in this case the main concepts of the method, which are fairly straightforward. Ur signifies the urge to move beyond familiar techniques when they do not fit our needs. Lastly, the energy and effort I am putting into this project show up with Nion.

The second position ended up empty. In this case, there is nothing specific working against this project’s success. This should not be misinterpreted as automatic success. Rather, it is more like running unopposed in an election. If I sit at home and do not put in the work necessary to qualify as a candidate, I will not be in the election and thus despite the lack of an opponent I still will not win.

The third position highlights factors that will tilt the odds even more in favor of success. Ailm is a reminder to consider perspective, particularly that of the reader. An explanation that is clear to me but gibberish to anyone else is not a helpful one. Uillean hints that the flexibility to vary this method is an important feature since the basic method may not work for everyone. Some seers may understandably balk at the prospect of Hagalaz or the Tower turning up multiple times in a single reading. Going along with the flexibility of the method, it would also help to be flexible in writing this article and responding to feedback I receive on early drafts.

Overall, the reading is extremely favorable. Hopefully I have managed to reflect its advice in what I have written, though the readers will have the final word on how well I have done so.

Practical Considerations

The Lansing method can be used with any sortilege system of divination – that is, one where symbols are drawn randomly from a set. In practice, because the method requires many rounds of randomization, it works better with a set of tokens that can be quickly shaken in a bag. I find the reduction step takes just a couple minutes for each position with my ogham set, for example. With tarot and other card-based systems, you may spend much more time shuffling. This happens because for each round of the reduction step you need to randomize the upright/reversed orientation of the cards, whereas shuffling normally is just concerned with randomizing their order.

Something else you might find helpful is defining a specific area for this process, such as a table top or casting cloth. Anything outside that area is out of bounds and does not count. That way, any symbols that jump out of the bag while shaking, roll off the table when emptying the bag, or otherwise wander off will just go right back into the mix and get re-done. Alternatively, deciding in advance to accept the symbols however they land is completely valid as well, but personally I find it easier to grab tokens as soon as they start rolling off rather than chasing them down all over the room.

Part of the reason I disregard “volunteer” or “wandering” symbols when using the Lansing method – though I do pay attention to them otherwise – is the sheer number of times the set gets handled during the process. If I go through, say, seven reduction cycles for a particular position, and a symbol rolls off one of the seven times, that does not seem like something that probably has any meaning beyond the random ways my circular tokens might move when emptied onto a table. In contrast, if I do a more traditional reading where I grab one symbol per position, having an extra symbol jump out and “volunteer” during that single draw has more meaning.

Properties of the Reduction Step

The systematic nature of the Lansing method allows us to quantify its properties, some of which may seem counterintuitive at first. For example, as long as you start the reduction step with at least one symbol, there is always a 50% chance of ending up with an empty position. (If you start the reduction step with no symbols – a possibility if you use the at most once variant – that chance would of course be 100%.)

In addition, the average number of symbols per position only loosely depends on the number you start with. If you start the reduction step with a single symbol you will average half a symbol per position, since half the time you keep that symbol and half the time you have an empty position. If you start with two symbols, you will average three-quarters of a symbol per position.

Although it seems like the average should keep growing as the symbol set grows, the result for three or more symbols is more or less the end of it. For practical purposes, starting the reduction step with three or more symbols leads to an average of about 6/7 symbol per position. If you calculate the exact value you will find it fluctuates ever so slightly as the number of starting symbols increases, but not enough to notice when applying the method.

The number of rounds of reduction you will need to go through on average, however, does keep increasing with the number of symbols. Fortunately, it does so rather slowly. A set of runes (24 symbols) or ogham (25 symbols) will take a bit less than five rounds of reduction on average. A full tarot deck (78 cards) would average just over six rounds, despite it having more than three times as many symbols. If you somehow have a set of tarot that is based on tokens of some kind and not cards, then the Lansing method would be almost as fast as with oghan or runes. The slowness with tarot comes from all the shuffling, not the number of rounds in the reduction step.

A More Complex Variation

Readers who are just becoming familiar with the basic Lansing method and the variants presented earlier can skip this section and come back to it later without loss. For seers who want even more ways to adapt their divination methods to various situations, though, there is one further dimension of flexibility worth discussing.

Consider again an astrological chart. Casting a chart for a particular time is equivalent to randomly assigning some number of celestial bodies – such as the sun, the moon, planets, and asteroids – to the houses. 8 bodies assigned to 12 houses with equal probability will on average fill half of them. The vintage chart from the introduction with 7 filled houses (though by 9 bodies instead of 8), then, is a fairly typical result. This 50% fill rate also corresponds nicely to the reduction step.

However, as we include more bodies on the chart, we will tend to fill more of the houses. 16 bodies, for example, will fill 9 houses on average, and the number keeps creeping closer to the full 12 as the number of bodies increases. The reduction step, however, always gives a 50% chance of filling a position, no matter how many symbols you start with. What if that 50/50 chance of an empty position is not what we want?

To see how we might adjust that probability, we can think of the reduction step as a combination of two separate decisions: which positions to fill or leave empty, and which symbols to select for the non-empty positions. A seer could use some other method to determine which positions to leave empty, then just skip over those positions entirely for the rest of the process. The methods for selecting the empty positions are limited only by the seer’s creativity. Alternatively, you can decide that none of the positions should be empty.

Once you have made that decision, you can proceed with the rest of the method. If you use a variant with the allocation step (the exactly once or at most once variants), you would reroll any result allocating a symbol to an empty position.

If you use a variant with the reduction step (the unrestricted or at most once variants), since you have already determined which positions are empty you would change the process slightly to avoid that outcome. Instead of eliminating all the remaining symbols when they all come up reversed, you end the reduction at that point and keep all those symbols. In other words, you treat an all-reversed outcome as if it were an all-upright one. To ludicrously stretch our earlier party analogy, if all the remaining guests try to decline simultaneously, we guilt trip them into coming anyway.

I am presenting this more complex variation in case some readers find it helpful. In general, I would expect that in most situations where the traditional one symbol per position approach does not suffice, the simpler variants I presented earlier will. However, in those instances where the simpler variants do not suffice, the seer at least has these additional options to consider.

Final Thoughts

Although traditional methods work well in many cases, sometimes a different approach would be better. The techniques of the Lansing method give practitioners additional options in those situations, complementing the variety of systems and spreads already in use. This broader set of techniques allow for the specific approach to be tailored to the situation at hand. In addition, hopefully with these techniques practitioners can go deeper with their craft and better serve themselves and their communities. Bonan ŝancon!

Appendix: The Issue of Replacement in Divination

There is an issue that the Lansing method touches on indirectly, namely, whether sortilege divination should be done with replacement or not. However, this goes beyond the Lansing method, as even the traditional method faces this issue, so it is worth addressing separately.

The underlying question comes down to whether a symbol can appear in the chart more than once (the “with replacement” case) or not. This can happen either by having duplicate sets of symbols – with multiple seers using separate sets or a single seer using each set in turn – or by using a single set but returning each position’s symbols before drawing the next position’s. In practice, the latter case (one seer and one copy of the symbol set) is probably the most common situation.

In my experience, sortilege divination is very rarely done with replacement. In other words, the outcome Raido / Raido / Hagalaz, for example, could not occur because when drawing the symbol for the second position the Raido rune is no longer in the bag to be chosen. However, that was precisely the outcome in the one publicly documented example I know of featuring a with-replacement divination (Thomas). Because many rituals are not published publicly and many rituals do not use with-replacement divination, that is the only example I know of.

Fortunately, that one example demonstrates the problem. Why should certain divinatory messages be impossible for a single seer to receive, but become possible with multiple seers, or with multiple copies of a symbol set? It does not matter how many seers or sets we have if we use a with-replacement approach, though; we can end up with Raido / Raido / Hagalaz and similar outcomes regardless.

The with-replacement approach also allows for finer shades of meaning and emphasis in the message. Compare where the emphasis would have landed if the message had been, for example, Raido / Hagalaz / Hagalaz instead – the same two runes, but producing a very different tone.

That said, the with-replacement approach does have some drawbacks when you only have one copy of the symbol set available. First, unless the seer writes down the symbols as they are drawn, there is the possibility of forgetting or misremembering some of them by the end of the process. It may sound silly to worry about remembering, say, three symbols for a minute or two, but keep in mind the seer’s state of consciousness likely differs from their everyday mental state. Pen and paper solve this problem if multiple copies of the symbol set are not available, but it does add one more thing to plan for.

Another drawback is that some individuals and groups record their divinations by taking photos of them, which is not possible when reading with replacement unless you have duplicate sets or settle for a picture of the seer’s written notes (or for taking multiple photos). It may sound like another minor thing, but the human element is one key element of ritual and many of us respond much more strongly to an aesthetically pleasing photograph showing the symbols laid out nicely than to a written description of the same reading. Without that visual record, some of the resonance of that ritual later on is lost.

Thus, I will freely admit that with-replacement methods are not a perfect alternative. However, I suspect seers may benefit from using them more often than they currently do, even for the traditional approach of one symbol per position.

Works Cited

Sepharial. “Astrology: How to Make and Read Your Own Horoscope.” Project Gutenberg, 25 September 2014, www.gutenberg.org/files/46963/46963-h/46963-h.htm.

Thomas, Kirk. “Establishing ADF's Initiatory Current.” Ár nDraíocht Féin, 15 July 2011, www.adf.org/articles/working/initiatory-current.html.

Currently, something of a divide exists in divination practices. On the one hand we have astrology. Consider this natal chart, for example (Sepharial). In the twelfth house, located on the left directly above the horizontal ascendant line, we find both the moon and Mars. The eleventh house just above it, though, is empty, as are three consecutive houses on the right. These kinds of arrangements are typical in natal charts, where some houses may have multiple planets while others have none.

On the other hand, with sortilege methods of divination, such as tarot, runes, and ogham, the typical techniques produce a different pattern. The layout has one or more positions, and one symbol is drawn for each. In a Celtic cross spread, for example, one symbol is drawn for each of the ten positions. The key difference is that each position always has exactly one symbol, unlike in astrology. Often this is fine for providing the answers we need.

Sometimes, however, we may want a more detailed picture. We may find ourselves in a situation where some aspects are influenced by many factors and others by few or none. One quick alternative that works with sortilege methods is to grab a handful of tokens instead of just one for each position. Again, sometimes that may be enough. Other times, though, we may want to use a more systematic approach, especially one that allows for empty positions.

The method introduced here can meet those needs. The basic method allows for positions to have zero, one, or multiple symbols. The variations discussed later allow the seer to further adjust the method to meet the needs of that particular divination. In honor of the city where I first used this method, I refer to it and its variants as the Lansing method.

What You Need

The Lansing method works with any set of divination symbols where you can tell reversed symbols from upright ones. One of the intermediate steps, which will be explained shortly, will rely on separating upright and reversed symbols. You do not have to read reversals in your final interpretation, though you certainly can if you want.

You will also need some way of randomizing the symbols, including their upright/reversed orientation. For symbols on pieces of wood or stone, a bag large enough to thoroughly mix them with a shake works. For symbols on cards, you will need to shuffle them carefully to ensure you randomize the orientations.

Lastly, you need to decide on a spread layout. This could be just a single position for a quick reading, a three position past/present/future layout, the 12 astrological houses, or whatever other spread makes sense for your purpose.

Basic Method

The basic process consists of two steps, which you will repeat for each position in your layout. The first step, the reduction step, will start with your full set of symbols and repeatedly eliminate any of them not needed for that position. The second step, the casting step, produces the final result.

To understand the reduction step, a useful analogy is sending out invitations to a party. Initially, everyone gets an invitation and is a potential guest. Some will decline the invitation immediately due to schedule conflicts or other reasons. Those folks are no longer potential guests. Based on those responses, other people may decline as well – if someone knows their spouse or best friend is not going, or if the person they rely on for a ride is not going, they are likely to decline the invitation too.

After each cycle of responses, as more people back out of the party, the guest list shrinks, until one of two things happens. It may be that eventually everyone declines the invitation; no one will be coming to that party. The party may be a failure in our analogy, but in divination this is not a problem. Just as many of us have empty houses in our natal charts, the more general case is no different – in the chart we are casting, there simply will not be anything happening in that particular position.

The other possibility is that after a cycle of responses, no one new has backed out of the party. This means we have a final list of guests, since no one left on the list had a reason to back out. All of the remaining symbols, then, will fill that position in our layout.

So, to bring our analogy back to divination, shake all of your symbols in your bag or shuffle all your cards together. Ask, “which symbols wish to remain in the casting for the first house?” or whatever appropriate description of that position fits your layout. Then empty out your bag or stop shuffling. At this point, just look at whether symbols are upright or reversed. For this purpose, we read upright as “yes” and keep those symbols; reversed symbols have responded “no” and get removed from this position. We repeat this process on an ever shrinking set of symbols until we reach one of the two endpoints: either all symbols get removed – meaning we move on and start fresh at the next position – or we get a set of symbols that are all upright. Either way, the reduction step ends for that position.

You only need the casting step if you actually read reversals in your divination. The reduction step used uprights and reversals as a simple yes/no system, but that does not mean you need to consider reversals in your final interpretation. If you intend to disregard reversals, you are done with this position – you know which symbols are there, so write them down and move on to the next position.

If you do read reversals, though, we need to do one last shake up of the bag. Otherwise, we could never end up with reversed symbols because of how the reduction step works. Put the remaining symbols in your bag, shake it up, say “I am now casting the reading for the first house” or similar words to that effect, and turn them out. The set of symbols remains the same, but this extra step has reintroduced the possibility of reversals in your reading.

Continue through each position, reducing (starting with the full set for each position) and – if needed – casting, until you complete your layout. Once you have filled each position, perhaps with blank spaces for some, you have completed the chart. It is then up to you to interpret the resulting symbols for each position.

Variations

Applying the basic method, a particular symbol in your divination set may appear in one position, multiple positions, or may not appear in your chart at all. For many purposes, this may serve our purposes fine. However, if you want something more akin to an astrological natal chart, the method can be adapted to achieve this.

There are three outcomes we can accomplish easily. Using the basic process discussed earlier, each symbol is unrestricted in how many times it appears (perhaps nowhere, perhaps multiple places). Alternatively, we can restrict symbols to either appear exactly once or at most once in the chart, if those would suit the reading better. Either way, we accomplish this by adding one extra step before we start reducing: the allocation step. Unlike the reduction and casting steps, we only do the allocation step once for the entire layout, not position by position.

With the allocation step, we assign each symbol to exactly one position. The multi-sided dice used for role-playing games work well for this – a 12-sided die (“d12”) works perfectly for the 12 astrological houses, for example. If you do not have such dice, a phone or computer can also provide random numbers. Just roll the die for each symbol, and the result is the position it gets allocated to.

For the at most once variant, proceed with the reduction step as before, except starting with just the symbols allocated to each position instead of the entire set. For the exactly once variant, skip the reduction step. In any case, finish each position with the casting step if you want reversals in your layout.

As a visual summary, this flow chart shows the steps for each variant.

There is one minor consequence of this process that might be helpful to point out. Since the exactly once variant does not use the reduction step, you can apply it to systems that do not have an upright/reversed distinction. For example, astrological charts effectively use that variant, where the relative positions in the sky serve as the allocation step.

Example

I used the basic Lansing method to cast a chart for the success of this article. I read reversals, but all the ogham happened to come out upright anyway in this case. My layout was simple. The first position represents factors helping the success of this article in spreading knowledge of the technique. The second position represents factors hindering its success. The third is the hinge or the pivot – what factors will decide the balance between success or failure.

Helping factors: Ailm, Ur, Nion

Hindering factors: none

Deciding factors: Ailm, Uillean

Encouragingly, three factors are helping drive the success of this project. Ailm points to the big picture, in this case the main concepts of the method, which are fairly straightforward. Ur signifies the urge to move beyond familiar techniques when they do not fit our needs. Lastly, the energy and effort I am putting into this project show up with Nion.

The second position ended up empty. In this case, there is nothing specific working against this project’s success. This should not be misinterpreted as automatic success. Rather, it is more like running unopposed in an election. If I sit at home and do not put in the work necessary to qualify as a candidate, I will not be in the election and thus despite the lack of an opponent I still will not win.

The third position highlights factors that will tilt the odds even more in favor of success. Ailm is a reminder to consider perspective, particularly that of the reader. An explanation that is clear to me but gibberish to anyone else is not a helpful one. Uillean hints that the flexibility to vary this method is an important feature since the basic method may not work for everyone. Some seers may understandably balk at the prospect of Hagalaz or the Tower turning up multiple times in a single reading. Going along with the flexibility of the method, it would also help to be flexible in writing this article and responding to feedback I receive on early drafts.

Overall, the reading is extremely favorable. Hopefully I have managed to reflect its advice in what I have written, though the readers will have the final word on how well I have done so.

Practical Considerations

The Lansing method can be used with any sortilege system of divination – that is, one where symbols are drawn randomly from a set. In practice, because the method requires many rounds of randomization, it works better with a set of tokens that can be quickly shaken in a bag. I find the reduction step takes just a couple minutes for each position with my ogham set, for example. With tarot and other card-based systems, you may spend much more time shuffling. This happens because for each round of the reduction step you need to randomize the upright/reversed orientation of the cards, whereas shuffling normally is just concerned with randomizing their order.

Something else you might find helpful is defining a specific area for this process, such as a table top or casting cloth. Anything outside that area is out of bounds and does not count. That way, any symbols that jump out of the bag while shaking, roll off the table when emptying the bag, or otherwise wander off will just go right back into the mix and get re-done. Alternatively, deciding in advance to accept the symbols however they land is completely valid as well, but personally I find it easier to grab tokens as soon as they start rolling off rather than chasing them down all over the room.

Part of the reason I disregard “volunteer” or “wandering” symbols when using the Lansing method – though I do pay attention to them otherwise – is the sheer number of times the set gets handled during the process. If I go through, say, seven reduction cycles for a particular position, and a symbol rolls off one of the seven times, that does not seem like something that probably has any meaning beyond the random ways my circular tokens might move when emptied onto a table. In contrast, if I do a more traditional reading where I grab one symbol per position, having an extra symbol jump out and “volunteer” during that single draw has more meaning.

Properties of the Reduction Step

The systematic nature of the Lansing method allows us to quantify its properties, some of which may seem counterintuitive at first. For example, as long as you start the reduction step with at least one symbol, there is always a 50% chance of ending up with an empty position. (If you start the reduction step with no symbols – a possibility if you use the at most once variant – that chance would of course be 100%.)

In addition, the average number of symbols per position only loosely depends on the number you start with. If you start the reduction step with a single symbol you will average half a symbol per position, since half the time you keep that symbol and half the time you have an empty position. If you start with two symbols, you will average three-quarters of a symbol per position.

Although it seems like the average should keep growing as the symbol set grows, the result for three or more symbols is more or less the end of it. For practical purposes, starting the reduction step with three or more symbols leads to an average of about 6/7 symbol per position. If you calculate the exact value you will find it fluctuates ever so slightly as the number of starting symbols increases, but not enough to notice when applying the method.

The number of rounds of reduction you will need to go through on average, however, does keep increasing with the number of symbols. Fortunately, it does so rather slowly. A set of runes (24 symbols) or ogham (25 symbols) will take a bit less than five rounds of reduction on average. A full tarot deck (78 cards) would average just over six rounds, despite it having more than three times as many symbols. If you somehow have a set of tarot that is based on tokens of some kind and not cards, then the Lansing method would be almost as fast as with oghan or runes. The slowness with tarot comes from all the shuffling, not the number of rounds in the reduction step.

A More Complex Variation

Readers who are just becoming familiar with the basic Lansing method and the variants presented earlier can skip this section and come back to it later without loss. For seers who want even more ways to adapt their divination methods to various situations, though, there is one further dimension of flexibility worth discussing.

Consider again an astrological chart. Casting a chart for a particular time is equivalent to randomly assigning some number of celestial bodies – such as the sun, the moon, planets, and asteroids – to the houses. 8 bodies assigned to 12 houses with equal probability will on average fill half of them. The vintage chart from the introduction with 7 filled houses (though by 9 bodies instead of 8), then, is a fairly typical result. This 50% fill rate also corresponds nicely to the reduction step.

However, as we include more bodies on the chart, we will tend to fill more of the houses. 16 bodies, for example, will fill 9 houses on average, and the number keeps creeping closer to the full 12 as the number of bodies increases. The reduction step, however, always gives a 50% chance of filling a position, no matter how many symbols you start with. What if that 50/50 chance of an empty position is not what we want?

To see how we might adjust that probability, we can think of the reduction step as a combination of two separate decisions: which positions to fill or leave empty, and which symbols to select for the non-empty positions. A seer could use some other method to determine which positions to leave empty, then just skip over those positions entirely for the rest of the process. The methods for selecting the empty positions are limited only by the seer’s creativity. Alternatively, you can decide that none of the positions should be empty.

Once you have made that decision, you can proceed with the rest of the method. If you use a variant with the allocation step (the exactly once or at most once variants), you would reroll any result allocating a symbol to an empty position.

If you use a variant with the reduction step (the unrestricted or at most once variants), since you have already determined which positions are empty you would change the process slightly to avoid that outcome. Instead of eliminating all the remaining symbols when they all come up reversed, you end the reduction at that point and keep all those symbols. In other words, you treat an all-reversed outcome as if it were an all-upright one. To ludicrously stretch our earlier party analogy, if all the remaining guests try to decline simultaneously, we guilt trip them into coming anyway.

I am presenting this more complex variation in case some readers find it helpful. In general, I would expect that in most situations where the traditional one symbol per position approach does not suffice, the simpler variants I presented earlier will. However, in those instances where the simpler variants do not suffice, the seer at least has these additional options to consider.

Final Thoughts

Although traditional methods work well in many cases, sometimes a different approach would be better. The techniques of the Lansing method give practitioners additional options in those situations, complementing the variety of systems and spreads already in use. This broader set of techniques allow for the specific approach to be tailored to the situation at hand. In addition, hopefully with these techniques practitioners can go deeper with their craft and better serve themselves and their communities. Bonan ŝancon!

Appendix: The Issue of Replacement in Divination

There is an issue that the Lansing method touches on indirectly, namely, whether sortilege divination should be done with replacement or not. However, this goes beyond the Lansing method, as even the traditional method faces this issue, so it is worth addressing separately.

The underlying question comes down to whether a symbol can appear in the chart more than once (the “with replacement” case) or not. This can happen either by having duplicate sets of symbols – with multiple seers using separate sets or a single seer using each set in turn – or by using a single set but returning each position’s symbols before drawing the next position’s. In practice, the latter case (one seer and one copy of the symbol set) is probably the most common situation.

In my experience, sortilege divination is very rarely done with replacement. In other words, the outcome Raido / Raido / Hagalaz, for example, could not occur because when drawing the symbol for the second position the Raido rune is no longer in the bag to be chosen. However, that was precisely the outcome in the one publicly documented example I know of featuring a with-replacement divination (Thomas). Because many rituals are not published publicly and many rituals do not use with-replacement divination, that is the only example I know of.

Fortunately, that one example demonstrates the problem. Why should certain divinatory messages be impossible for a single seer to receive, but become possible with multiple seers, or with multiple copies of a symbol set? It does not matter how many seers or sets we have if we use a with-replacement approach, though; we can end up with Raido / Raido / Hagalaz and similar outcomes regardless.

The with-replacement approach also allows for finer shades of meaning and emphasis in the message. Compare where the emphasis would have landed if the message had been, for example, Raido / Hagalaz / Hagalaz instead – the same two runes, but producing a very different tone.

That said, the with-replacement approach does have some drawbacks when you only have one copy of the symbol set available. First, unless the seer writes down the symbols as they are drawn, there is the possibility of forgetting or misremembering some of them by the end of the process. It may sound silly to worry about remembering, say, three symbols for a minute or two, but keep in mind the seer’s state of consciousness likely differs from their everyday mental state. Pen and paper solve this problem if multiple copies of the symbol set are not available, but it does add one more thing to plan for.

Another drawback is that some individuals and groups record their divinations by taking photos of them, which is not possible when reading with replacement unless you have duplicate sets or settle for a picture of the seer’s written notes (or for taking multiple photos). It may sound like another minor thing, but the human element is one key element of ritual and many of us respond much more strongly to an aesthetically pleasing photograph showing the symbols laid out nicely than to a written description of the same reading. Without that visual record, some of the resonance of that ritual later on is lost.

Thus, I will freely admit that with-replacement methods are not a perfect alternative. However, I suspect seers may benefit from using them more often than they currently do, even for the traditional approach of one symbol per position.

Works Cited

Sepharial. “Astrology: How to Make and Read Your Own Horoscope.” Project Gutenberg, 25 September 2014, www.gutenberg.org/files/46963/46963-h/46963-h.htm.

Thomas, Kirk. “Establishing ADF's Initiatory Current.” Ár nDraíocht Féin, 15 July 2011, www.adf.org/articles/working/initiatory-current.html.